Androna, Syria – The Byzantine Bath

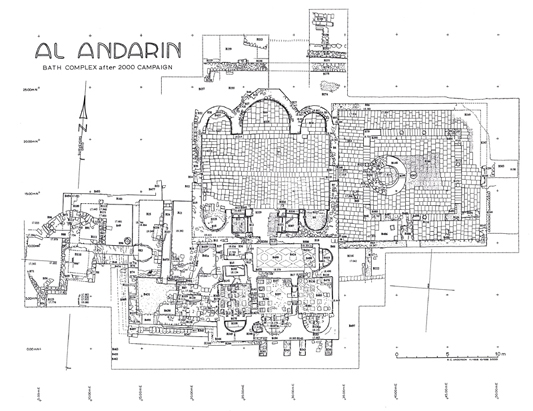

The basalt and brick bath, built in ca. 560 by Thomas (who also constructed the large kastron opposite in 558-9), according to a Greek verse inscription on its lintel, was excavated 1998-2001. Its plan, ca 23 x 40 m, is divided into four parts: a peristyle entrance court; a north frigidarium with a symmetrical layout, five apses and two rectangular pools; a south tepidarium and a caldarium comprised of a brick complex of apsed rooms with six semicircular and rectangular pools; and a west service area. Architecturally, it is larger than the village baths of the north Syrian Limestone Massif. It more closely resembles in layout the Byzantine city bath at Zenobia on the Euphrates and the Umayyad baths at Androna and at Qusayr Amra in Jordan.

|

|

| Photo by M. Mango | Drawing by D. Hopkins |

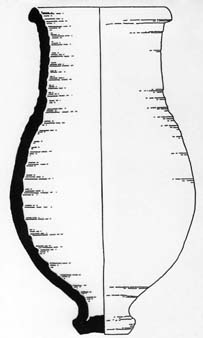

The water of the Byzantine bath at Androna was supplied by a saqiya-operated well situated in the west service area and a carafe-shaped cistern in the entrance court. While the former filled the bath’s pools, the latter provided drinking water. The jars used on a chain (pot garland) to lift water above ground level account for nearly half the diagnostic sherds of pottery found in the bath. Water lifted from the well was conveyed to one or more water tanks positioned above the bath. Used water was drained from the pools by two systems, one running to the south of the bath, the other to the north, both apparently emptying into a second, disused well 11 m deep. The cistern water was collected from the roof of the peristyle entrance court via vertical pipes at its four corners.

By far the greatest amount of decorative material found in the bath was 500 kg of 19 types of marble (over half of it Proconnesian from the Sea of Marmara) and other decorative stones used for pavements, door mouldings, champlevé carving, other wall revetments, opus sectile work, the carved enclosures of the cold pools, a marble fluted basin, and a small marble statue. The south rooms had white tessellated pavements. The entrance court was decorated with figural paintings, of which only the lower parts remain on the west wall. The frigidarium was at least partly decorated with glass wall mosaics, while the caldarium had brightly coloured wallpaintings of abstract patterns and Greek inscriptions enclosed in wreaths.

|

|

Photos by M. Mango

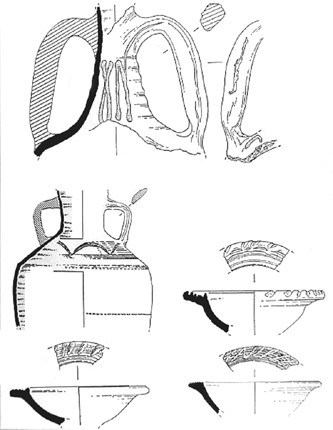

Excavated finds appropriate for a bath include ceramic spindle-shaped unguentaria for oil, some stamped, and numerous glass perfume flasks and small drinking goblets. Altogether, the pottery is mostly Late Roman/Byzantine, with some of the transitional period from Late Byzantine to Umayyad. Nothing is definitely Abbasid. Imported wares include African Red Slip Ware and Late Roman C and D Wares. Local coarse wares include small buff bowls with decorated rims and Brittle Ware. Amphorae included Egyptian types and Riley Carthage Late Roman 1 as well as local painted and combed buff amphorae.

|

|

Drawings by D. Hopkins (c) All rights reserved.

The bath remained in use, probably for several decades, judging by the condition of the furnaces, the amount of limescale deposits, and successive layers of wallpaintings. Eventually, when the bath went out of use (possibly following a partial structural collapse), various industrial activities were installed there, including a metal workshop in the tepidarium and a kiln in the entrance court the aisles of which were partitioned for yet other purposes; another kiln was built outside the west door of the frigidarium. This conversion of the building may have occurred in the Umayyad period, judging from the excavated pottery. In this period another bath of similar size and plan was built nearby and has now been excavated by the Syrian team. This late bath incorporated several Byzantine inscriptions in its floors and walls and its water was apparently supplied by the well of the Byzantine bath uphill from it.

Participants

The excavated Byzantine bath and reservoirs were planned by Richard Anderson with the assistance of Dr. Tassos Papacostas, Dr. Jonathan Bardill and Dr. Lukas Schacher, with contributions by Simon Greenslade, Sarah Leppard, and Stuart Randall. The bath and reservoirs were excavated by, notably, Amanda Claridge, as well as Katherine Blythe, Paul Clark, Simon Greenslade, Cassian Hall, Prof. Robert Hoyland, Dr. Carrie Hritz, Sarah Leppard, Antonietta Lerz, Dr. Marlia Mango, Prof. Cyril Mango, Dr. Anne McCabe, Dr. Maria Parani, and Dr. Nigel Pollard.

Finds were drawn by Dave Hopkins and processed by Priscilla Lange, Dr. Maria Parani, and Natalija Ristovska.

The following material excavated in the Byzantine bath is being studied:

The Greek inscriptions, by Prof. Cyril Mango, Oxford University.

The marble, by Dr. Olga Karagiorgou, Academy of Athens.

All pottery, by Dr. Nigel Pollard, School of Humanities, Swansea University.

The Brittle Ware pottery, by Dr. Agnès Vokaer, Centre de Recherches Archéologiques, l'Université Libre de Bruxelles.

The metallurgical finds of the metal workshop installed in the bath

tepidarium, by Chris Salter, Materials Department, Oxford University.

For organic material see Landscape Study section.